[ad_1]

“I thought I was going to die.” We’ve all heard this phrase. Many of us have said it—and usually haven’t meant it literally. But when it’s not hyperbole, when death is actually staring you in the face, there’s terror coiled in those seven words. Yet, in the world of extreme athletics, where operating on the do-or-die edge is part of the deal, fear may actually serve a practical purpose, too. It can allow us to clearly recognize what we’re facing, dig deep, focus on a specific skill set, and confidently make it through.

I’ve dabbled in risky sports all my life. I train constantly and am one of the lucky ones with a biology that translates fear into focus, calm, and an ability to excel under pressure. That doesn’t mean I’m not afraid. Fear tightens my chest and tunnels my vision. I feel it before I rope up for a climb, or rappel into a steep couloir on skis. But I also know that it will lead to a “flow state” where muscle memory will take over, and where a solid sense of judgement will help me deal with (or avoid) a variety of dangerous situations. Paradoxically, this often stems from fear.

Related: The 18 Coolest Adventurers in the World Right Now

On three occasions, despite good intentions and careful calculations, I faced life or death situations. One was on a disabled catamaran in the Atlantic, violently tossed by wind and waves, miles from shore. Another happened on the second pitch of a frozen waterfall that had suddenly turned to rushing water right below the surface—my axes and crampons sliding through the thin shell like a knife through butter. Recently, in Wadi Rum, Jordan, my climbing partner and I got off route on a vast 900-foot-high, quarter-mile wide sandstone dome. It was like being lost in a vertical Sahara with no fixed anchors, no solid gear placements, and no option for retreat or rescue. It was the classic “you fall, we die” scenario.

Fortunately, on all three occasions, I had the training, focus, and luck to pull through. Sadly, I have many friends who weren’t so fortunate, so I know that fear isn’t groundless. This winter, I was skiing in the big mountain mecca of La Grave, France, with a friend who had sufficient technical skills. But the avalanche risk, exposure, and lack of room for error made her edgy. She took a scary fall, not due to a deficit of talent but because fear caused her to panic and make mistakes.

Later, she asked me how I handle fear. My initial response was trite: “You just endlessly review the mission, do a go/no-go analysis, trust your training, and commit.” But I was intrigued with the question. We discussed practice, baby steps, not panicking, making adrenaline your friend, maintaining that hyper-vigilant focus until you’re 100 percent safe, remembering to breathe, relying on muscle memory, and never forgetting that you have to be in the mood for what you’re doing.

Related: Best Thrill-Seeking Activities for Adrenaline Junkies

For me, handling fear involves long periods of training and long periods of psyching myself up. When the time comes, if I’m in the zone, I commit—but I always have multiple backup strategies, including “just say no.” There’s always tomorrow for those who wait.

It’s important to be comfortable with fear and not start off at the edge of your ability. You build up not only your skill level, but your ability to assess risk. You don’t jump into free soloing, big mountain skiing, or wingsuit flying. It’s baby steps. You can still get killed during baby steps, but generally, your risk assessment and ability to be calm under pressure improves with skill.

Handling fear is a big question, not only for extreme athletes, but for an individual who wants to try something new or step up their game. I decided it was worth talking to friends and colleagues at the top of their games who know quite a bit about risk and fear management. Here’s what they had to say.

Courtesy image

1. Determine if It’s Justified and Let It Help You Make Informed Decisions

Alex Honnold: Rock Climber

Alex Honnold is arguably the world’s most accomplished rock climber—best known for his 2,900-foot free solo climb (without a rope) of El Cap, a landmark achievement documented in the Academy Award-winning documentary, Free Solo. Honnold’s latest challenge was with sponsor, Dr. Squatch, where he embarked on thumb wrestling matches across the country. His Honnold Foundation provides marginalized communities around the world with access to solar power.

Of course I feel fear. There are tons of moments in climbing when I’m always a little afraid, whether it’s sport climbing or soloing over a roof. How I deal with fear depends on my objective—whether it’s a long and complicated matter or something fairly straight forward. It also depends on the nature of the fear I’m feeling. There can be that natural fear of the unknown, but there are justifiable, well-founded fears that need to be paid attention to. If I’m approaching an inherently difficult objective, then preparation is key. What helps me manage that type of fear is getting as capable as possible through training and planning.

I first try to determine if fear is justified. Sometimes the fear isn’t rational, so then I deploy different strategies of tapping into how I handle it. But a lot of times it is justified, then I go into risk mitigation and strategies to prevent something from going wrong. Climbing is an inherently dangerous sport, so everything, even something that might appear risk-free, has a risk attached.

Related: Fatherhood Changed How Alex Honnold Climbs, but Not How You’d Expect

You’re not always trying to overcome the fear, as a lot of times fear is telling you what to do—to make good, informed decisions. So much of climbing for me is a gut feeling. If you look up at a route and feel fear, then maybe it’s not what you should be doing that day. If I’m up on a route, and something happens after I’m already committed, it’s true that fear can start creeping up—and that’s the time to take some deep breaths.

In many ways, climbing is less of an extreme sport than others, like big wave surfing or wingsuit flying, because it’s comparatively slow. Generally, with climbing, there’s little time pressure to get things done. If you do nothing, you’ll be fine. So even with acute fear, you just need to chill, take your time, hang in there, and relax. If you have the fitness, you can take as much time as you need. No need to force it.

Courtesy image

When I was on the Free Solo film tour, I got into meditation, but I found I didn’t need it. It was nice, but when I’m climbing and outside full time, I don’t need it to focus or relax. I’m personally not troubled by an encumbered mind, anxiety, or random thoughts. I have the whole host of fears including public speaking and public displays of affection, but I think that by having spent my entire life climbing, I find it easier to manage those kinds of fears. I think that by managing the potentially life and death experiences of climbing, I’ve also found it increasingly easier to manage everyday things that might make me anxious. I’ve learned to differentiate between the physically risky experience of climbing and those fears that are more inconsequential in terms of outcome.

For example, when I agreed to do the Dr. Squatch Thumb Wrestling Challenge, I was nervous. I thought, “Oh man, they’re putting me out there with something I’m not at all good at.” I figured it would be a thing that might cause major embarrassment, but I went into it with an open heart. I didn’t win all my thumb wresting competitions, but I had fun, and it turned out to not be embarrassing. I’m not a good thumb wrestler. I probably have stronger thumbs than average, but I’m pretty slow.

Courtesy image

2. Practice, Practice, Then Jump In

Bubba Wallace: NASCAR Driver

Bubba Wallace drives for 23XI Racing for the 2023 NASCAR Cup Series. In 2021, he became the second Black driver to win in the Cup Series, with a victory at Talladega Superspeedway. In 2022, he earned his second victory at Kansas Speedway. He’s placed 2nd in the Daytona 500 and continues to break barriers, both in racing and racial injustice.

Generally, I’m kind of a no fear person. I just do it and enjoy the thrill. I don’t really feel fear before or during a race. I think if I had fear, I would not do it. But to dig deep into the issue, I guess the greatest fear is when I strap into my harness at the beginning of the race because I know I could die. The most frightening moment is when something goes wrong—like my 2018 crash at Pocono when my breaks gave out. In that moment, I really did think that was it.

Things can happen so quickly in a car that you don’t really have time to be afraid. You just work on everything you were taught—to be the best you can be. Recently, I spun out during qualifiers in Nashville. My first thought was that I didn’t want to go into the wall—as you don’t want to mess up the car.

Courtesy image

When you’ve been racing for 20 years, you get used to what you’re doing, know the risk is there, and continue to perform. You just keep relying on training and performance to carry the torch and not let risk hold you back.

On the other hand, if you start overanalyzing about every which way things can go wrong, it quickly becomes self-limiting. You’ve just got to do it. Period. You have to enjoy life to the fullest and not hold anything back, with no living in regret. I don’t like to think about something I could have done and didn’t. To me, that’s so much worse than moving forward and living life to the fullest. There are two sides to the coin: Not doing something because you’re worried and anxious, or jumping in. Take the latter route and chances are pretty good you’ll be okay.

IMAGO/Jonas Ericsson

3. Know the Risks, but Commit

Lindsey Vonn: Ski Racer

Lindsey Vonn is one of the most decorated American ski racers in history, the winner of four World Cup championships, 82 World Cup victories, numerous other titles, and an Olympic gold in downhill at the 2010 Winter Games—a first for an American woman. Having experienced devastating setbacks and brutal injuries during her career, Vonn’s courage and resolve to pick herself up and compete at the highest level is equally legendary. She’s also an author and founder of the Lindsey Vonn Foundation, which supports girls through scholarships, education, and athletics.

Fear has never stopped me from doing something. If I have butterflies, it usually means I’m doing something exciting and having a blast. What drew me to downhill was the thrill, speed, and risk—the danger of it. Even when I was coming back from injury, I didn’t feel fear because I knew how hard I had worked to get back to the starting gate, and I trusted that hard work. If I had thought, ‘What if I crash and injure myself again?’ I would have only limited myself. Being afraid, defensive, or hesitant in downhill is a dangerous place to be. Skiing with confidence and on the offense is a much safer approach and one that’s served me well.

Related: Seattle Mariners Mental Skills Coach Makes Players Resilient

I did experience anxiety when I was younger. Wanting and needing to perform to make it onto the team or make it to my first Olympics was a lot to handle on my own at age 16, but I developed ways of harnessing those emotions and using them to my advantage. Emotions can either help you or hurt you. It just depends on how well you can wield them.

I look at it very analytically. If I’m nervous or scared, will I perform? Most likely not. So, what’s the point of holding onto these emotions? I let go of them and accept that I could fail, but at least I know I did everything in my power to ski my best. If I do end up making a mistake and going into the fence at 80 mph, it happens so quickly that there’s almost nothing I can do but try and stay loose.

IMAGO/Jonas Ericsson

Fear lives in your mind. Be smart, know the risks of what you’re doing, but once you commit, commit. There’s no halfway when you’re pushing yourself. True growth comes when you push yourself out of your comfort zone, and then you can make that next level your new comfort zone. Keep pushing, keep growing, and don’t let fear prevent you from becoming your best self—because to be successful at anything, you have to believe in yourself. You can’t let fear or any other emotion distract you from what you want to achieve.

Courtesy image

4. If Fear Is Rooted in the Unknown, Educate Yourself

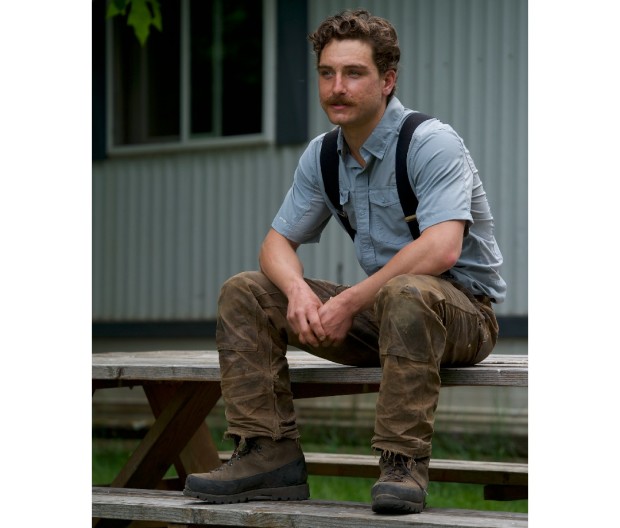

Dylan Efron: Adventurer and Outdoor Travel Host

Dylan Efron is an athlete and outdoor travel host who travels to faraway spots to promote adventure and raise environmental awareness. His latest documentary is about fear, shark diving, and how shark tourism is an important step in protecting these magnificent creatures from over-fishing.

Fear is often associated with the unknown. When I decided that I wanted to do some free diving with sharks, I was nervous—very nervous. There’s so much lore about sharks. The trick is to gain enough knowledge to take that first step.

To prepare for the film, I started free diving at 40 feet. After practice dives to the bottom, without sharks, I swam with lemon sharks near the top, reef sharks midway, and bull sharks at the bottom. I learned how the shark world works. The dominant shark is the one you have to pay attention to. A lemon shark may bump you on the way down, but you really have to pay attention to the bull sharks below. When you find the dominant shark, you need keep your eyes on it. In fact, you’re supposed to look a shark right in the eye—but what do you do when you have two of them coming at you, at your 9 and 3?

I had a checklist of things I should be doing—and not doing. No eggbeater arms, for example, while swimming. No having your hands out. You want to keep them close unless you need to redirect a shark, all while maintaining that crucial eye contact. If your neck doesn’t hurt from swiveling at the end of a dive, you’re doing it wrong.

Courtesy image

We did about 100 dives in a single day. The fear was very real. The hardest part of it was convincing myself that if a shark came at me, I would need to interact. You can’t start swimming away. Act fearful, and you’re acting like prey. That was the biggest mental hurdle. When that moment comes, when a 15-foot shark comes at you, you stand tall and reach your hand out to redirect. Looking at my little arm and hand, it seemed so skinny and feeble, but what I realized is that I could control my fear—and also that sharks aren’t there to kill you. You aren’t their prey. Then again, you can’t act like it.

I still have plenty of fear of sharks. It’s always there, especially when it comes to great whites when I’m surfing or spear diving off the California coast. But my experience has changed my tolerance of fear and comfort level with something that really scares me. While fear is real, in some situations you can’t be afraid—even with something that can kill you.

IMAGO/Aurora Photos

5. Let Fear Run Its Course and Empower You

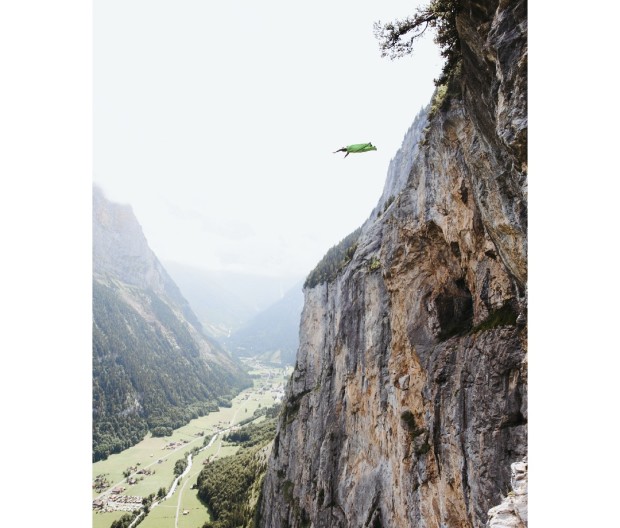

Matthias Giraud: BASE Jumper

Matthias Giraud is a professional skier, BASE jumper, and para-alpinist. He’s the world record holder of the highest ski BASE jump from the summit of Mont Blanc, and the only person to have ski-BASE jumped the Alps trilogy of Eiger, Matterhorn, and Mont Blanc.

I have a lot of fear. I just ski-BASE-d the most technical descent I’ve ever done and I was definitely afraid. The more I know about something, the more afraid I am—and that’s an integral part of what I do.

Before this ski-BASE, I had two nights of cold sweats and general freaking out. I called my girlfriend every two hours. My way of handling fear is to let it run through my body. I used to ignore it, put it in a box and do my thing, but then I realized that ignoring fear made me weak and less aware. Pushing aside fear is a form of disconnection. I believe it’s crucial to have fear as it’s a barometer of what you’re doing.

Orazio Guanieri

Fear and emotion are there to empower you, not impair you. Your emotional intelligence is needed to translate the data. It’s how you connect your modern mind with your lizard brain, to connect knowledge with instinct. Fear is the only emotion that will turn you into a survival machine. It’s actually your best friend because it can bring out your finest abilities.

I used to try to manage my fear, but I’ve come to believe trying to handle fear is BS—because fear is real and that emotional rollercoaster is normal. So, rather than ignoring it, I try to make it run its course. I strive for a calm, poised approach when in the mountains, but that doesn’t mean I’m not afraid.

It takes a lot of planning to quell natural emotions. When I don’t know the exact state of variables during an approach, I’m still in a hyper-alert, hyper-scared mode. Then, when I get to the top, I start to focus—because now I know what I’m dealing with. Then the fear diminishes, but I don’t forget that there are always surprises in snow conditions, wind, and other variables beyond my control. Most fear is the influx of uncertainty, but when you know what you’re dealing with, fear diminishes.”

Courtesy image

6. Determine if You’re Being Brave or Foolish

Gaylen Volkhausen: Kayaker

Gaylen Volkhausen is a professional kayaker. At age 17, he claimed the existing world record for the tallest waterfall descent on 127-foot Big Banana Falls in Veracruz, Mexico. He’s done first descents on Ecuador’s harrowing Zamora River as well as Washington’s 92-foot Rattlesnake Falls and a pair of back-to-back 90-foot drops on the White Salmon River. He works with The White Salmon Boat Library, a non-profit that supplies whitewater equipment to paddlers who could otherwise not afford it.

Fear is something I’ve lived with my whole life. I experience fear in kayaking, but even more so in everyday life. The fear I experience in kayaking is manifested through my knowledge that what I’m doing is dangerous and that my life is on the line if I make a mistake.

Ultimately, the fear is death. Putting yourself in life or death situations regularly puts death and fear in a scope where you can reach out and touch it and make friends with it through close proximity. For me, being highly aware of the risk of death makes me more appreciative of life. This fear is what gives me enjoyment in pushing my limits in a kayak. If I wasn’t scared, I would find a new hobby.

Courtesy image

“My go/no go mentality is this: If I know I can do it, I’m going to do it no matter how scared I am. If I don’t think I can pull it off, I don’t do it. I don’t have a no-fear mentality. I’m always fearful paddling dangerous whitewater—and I’m also cognizant of what my grandmother always said: “It’s a thin line between brave and foolish.” If you recognize the risk in something and still do it with that level of awareness, you’re enacting bravery. If you’re doing something dangerous without experiencing fear, then you may be falling into that foolish category.

IMAGO/China Foto Press

7. Learn the STOP Method

Bear Grylls: Survival Expert

Bear Grylls is a survival expert, adventurer, star of Man vs Wild among other shows, and a former British Army Special Forces op who has traveled the globe getting in (and out of) sticky situations. He currently serves as a U24 ambassador, the official fundraising platform of the Ukrainian government to protect, serve, and rebuild the country.

Fear is a big part of my life. It’s not my enemy, but something natural that keeps me sharp. Understandably, many people want to avoid fear, but I’ve found that by working through fear, I get into a state where all my senses are firing. When I’m put into a frightening situation, there’s an overload of adrenaline. I think the key to survival is developing that fear muscle or reaction. When you’re thrown into a scary situation, when that fear muscle isn’t strong, you get an overload of adrenaline. Gaining comfort with uncertainty and learning to adapt is the key to survival in frightening situations, whether they’re outdoor adventures or day-to-day life.

Related: Bear Grylls on Skydiving With Alex Honnold and Exploring the Jungle With Brie Larson

One way of dealing with fear is with the STOP method.

- S: Step back. Don’t give in to the moment of anxiety and instead act reflexively.

- T: Take a break from flight or fight mode, breathe, and get some distance from the fear.

- O: Observe, rather than fixate.

- P: Plan, and make a strategy to move forward.

People tend to get super focused on one specific thing, but the trick is to step back, look at your surroundings, look for escape routes, and analyze alternatives and options. It’s important to make sure you take stock of resources—and make sure you’re alert and have a strategy to move forward.

Courtesy image

8. Turn Inward and Check Yourself Before You Wreck Yourself

Tommy Ford: Ski Racer

Tommy Ford is one of the fastest men alive on skis, notching five World Championships and three Olympic Games with the U.S. Alpine Ski Team. While he’s won plenty, he’s also suffered serious crashes, broken bones, torn ligaments, sustained a serious concussion, and undergone numerous surgeries during a resilient career that’s seen him come roaring back with a recent World Cup Giant Slalom win and a team World Championship this past winter. He’s currently training for the 2023/24 season.

I feel fear almost every day, whether I’m skiing or not. In skiing, the fear of the unknown, failure, and injury are all constant companions on race day or even in training—given that they’re familiar thoughts and feelings that typically pass through my body. When these fears linger and trap my attention, I notice that my body becomes more tense, I’m more irritable, my muscles feel tired, I typically have less neuroplasticity, and my decision making suffers as a result.

For me, being aware of these physical and emotional signs serves as a reminder to bring my attention to the present moment. My go-to anchor is my breath because it’s omnipresent and has a calming effect on the vagus nerve, which goes straight to the brain. By persistently keeping my attention on my breath while recognizing the companions of fear, the thoughts seem to become less weighty. Then I’m able to trust myself and my abilities, approaching the race with more confidence.

Courtesy image

If you’re looking to get into a new sport or up your game, turn inward and check yourself before you wreck yourself. What I mean is, spend time to notice your thoughts coming and going so when it’s time to buckle down you’re more aware of what is happening internally so you can enjoy what’s happening externally. It’s when we get locked on to the tree that’s in front of us that we hit the tree rather than looking for a way around it. Fear is like the tree. If you stay locked onto it, you’ll likely have a hard time, but if you acknowledge it and have a look around, you’ll likely notice space for other options.

When learning something new it’s easy to get lost in your head when you start thinking about how you look, how quickly you’ve progressed, what could go wrong, or how badly this could hurt. While all of these ruminations are forms of fear, they have different weight. Injury is high up there on the scary scale. Winning is often up there, too, but in the form of potential failure. I typically don’t differentiate between these different fears, but returning from injury did get my attention more often. What I found was that when I tried to avoid thinking about injury, it just seemed to make me more and more scared.

It doesn’t much matter what’s driving fear. What matters more is that it’s addressed. Thankfully, books I’ve read and conversations I’ve had with friends, coaches, athletes, mental health/performance professionals, authors, artists and many others have shown me ways to live with fear while thoroughly enjoying life.

Courtesy image

9. Shift a Stressed Mindset to One of Stoke

JT Holmes: Stuntman

JT Holmes is an award-winning stuntman whose performances in a wingsuit, on skis, under a parachute, or in any number of motorized vehicles have been featured in Hollywood movies and countless commercials. He’s currently the director of business development at Peak Ski Company.

Everyone’s response to fear is different. When I’m embarking on something truly dangerous, I may well be terrified. I take a few breaths and try to calm down. I get to a point where I realize that this is about as calm as I’m going to get. I don’t mind a trembling hand or a racing heart. It’s okay. I have an analytical and very literal mind, so I’ll instinctually dissect what I’m doing and break it down into pieces. If I can assign a green light to each piece, then I feel comfortable relying on my logic rather than focusing on the symptoms of fear that my body is naturally experiencing.

Add in the pressure of, say, a helicopter dropping you off at the top of Eiger, or a film crew that costs a half-million a day, and there are consequences to backing down—so it’s critical to be prepared with an imperturbable plan. On a day with a big objective, in good conditions, there’s nearly no question that I’m going to launch. I’m going to do it. Once that decision is made it’s nice because I stop stewing over whether or not I’ll do something and focus entirely on what specific performance must occur to not die.

Now I’ve shifted from a stressed mindset to one of stoke. I’m thinking, “Oh yeah. This is the place to be!” You have to have enthusiasm and optimism to do something bold. There’s no room for a pessimistic or conflicted mind at the edge of a cliff. You have to want to be there. I want to risk my life in the name of movie making. I have no qualms over my motivations. They include ego, fun, passion for my craft, and money. If you’re not true with yourself and your motivations, then you risk second-guessing them at a critical moment. There’s no trepidation allowed. You have to be all-in. In fact, if you’re doing gnarly shit, a bit of cockiness is okay. Positive self-talk is healthy: “You got this, JT. All day long.”

If something goes terribly wrong in the middle of a stunt, then it’s time to not think but perform. You rely on your training, your instinct and you solve the problem. You can’t afford to focus on failure. You compartmentalize. There are times in life to be open with your feelings and respect them and give them bandwidth, and there are times to immediately fucking bury them in a black box never to be glanced at again. Move. Solve. Go. Now. No rearview mirrors.

The moment I take flight in a wing suit or ski off a cliff, a visual expanse reveals itself beneath me and I have a gut reaction: “good idea” or “bad idea.” If the “good idea” thing happens I charge and rip and have a blast. If the “bad idea” thing happens, I divert to previously visualized alternate or emergency plans. Instinct takes over. Things happen fast. In hindsight, when met with those “uh oh” moments, if I’ve prepared properly and my skills are sharp, the outcome is anywhere from “good, given the circumstances” to “I can’t believe I pulled that off flawlessly.” It’s true that some people do better when their frontal lobe is firing, but it’s a dangerous habit to make bets on skills you don’t normally have.

[ad_2]

Source link

Hi! I’m a dedicated health blogger sharing valuable insights, natural remedies, and the latest scientific breakthroughs to help readers lead healthier lives. With a holistic approach to wellness, I empower individuals with accessible and actionable content, debunking myths and offering practical tips for incorporating healthy habits.